Alternately, no marked acceleration in weight loss related to time to death could suggest that weight loss before death is driven by aging and age-related conditions not uniquely associated with time to death. Little research has attempted to identify the typical length, severity, and pattern of weight loss in the period preceding death.

A better understanding of weight loss patterns at the end of life would inform research on changes in energy balance in late life and the effects of obesity on health status in older persons. The purpose of this analysis was to characterize weight change in individuals who die at different ages and from different causes. Data were drawn from Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging participants. A description of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging sample is available elsewhere Male participants have been continuously recruited since , primarily from the Baltimore, Maryland—Washington, DC, area.

Women entered the study in ; too few have died to evaluate associations between weight and mortality in women.

Keeping your weight up in later life - NHS

Assessment intervals varied over the course of the study. Initially, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging assessments occurred every 2 years, but intervals have been revised to test participants younger than age 50 years every 4 years, those aged 50—79 years every 2 years, and those aged 80 years or older every year. Data included 6, observations of body weight across participants, for an average of 8. International Classification of Diseases , Ninth Revision, codes obtained from death certificates were available for deaths Only 7 heart failure deaths were identified; they were included with all cardiovascular deaths.

Weight in kilograms was measured on a standard balance scale after participants, wearing a hospital gown, had fasted overnight. Participants were classified by age years at death into 4 groups: 60—69, 70—79, 80—89, and 90 or older. Our goal was to identify a data-driven set of clinically useful and interpretable functions that described expected weight loss as death approached.

For the entire sample and for each age-at-death group, 5 models developed on the basis of theory and descriptive exploration of trajectories were compared by using the Akaike Information Criterion AIC for model fit. In models 3—5, knot points up to 25 years before death were examined. Confidence intervals for knot placements were estimated by using a likelihood ratio testing approach.

The last integer valued knots that were significantly different from the best-fitting knot at the 0. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate potential bias due to informative missingness in the last 3 years of life using 4 alternative imputation scenarios. Table 1 provides causes of death by age group. Among all ages, CVD was the most common, accounting for nearly half of all deaths. With increasing age, the frequency of other deaths increased, from Figure 1 provides weight by time to death for 30 randomly selected participants in each age-at-death group to visualize heterogeneity in individual weight change trajectories.

In spite of great variability in weight trajectories across individuals, progressively longer periods of weight decline are detectable with increasing longevity. Among individuals who died in their sixties, weight loss was largely confined to the last 5 years of life; among those who died at age 90 years or older, weight loss was evident at least 10 years before death for many individuals.

Weight in kilograms by time to death for male decedents from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, Maryland, — Residual error also decreased across models, with similar residuals found for models 4 and 5. Significant variability in both intercept and slopes was observed in all models.

- how to reduce stomach fat in males!

- will i lose weight eating watermelon!

- yoga to reduce lower abdominal fat!

Additional analyses tested the fit of each model in subgroups defined by age at death and cause of death. Fixed-effects results are shown for only the best-fit model Table 3. Model 5 had the best fit i. Model 5 also had the best fit for cancer deaths and other deaths. Although model 4 provided the best fit for cardiovascular deaths in all ages combined, model 5 provided the best fit for cardiovascular deaths within each age-at-death group.

Model 5 allows for 3 distinct periods of weight change postulated a priori using a spline model with 2 knots , including an early period of weight gain, a period of weight stability or moderate decline, and a period of accelerated weight decline before death. In the average model for all ages, the best-fitting inflection points were at 17 and 9 years before death.

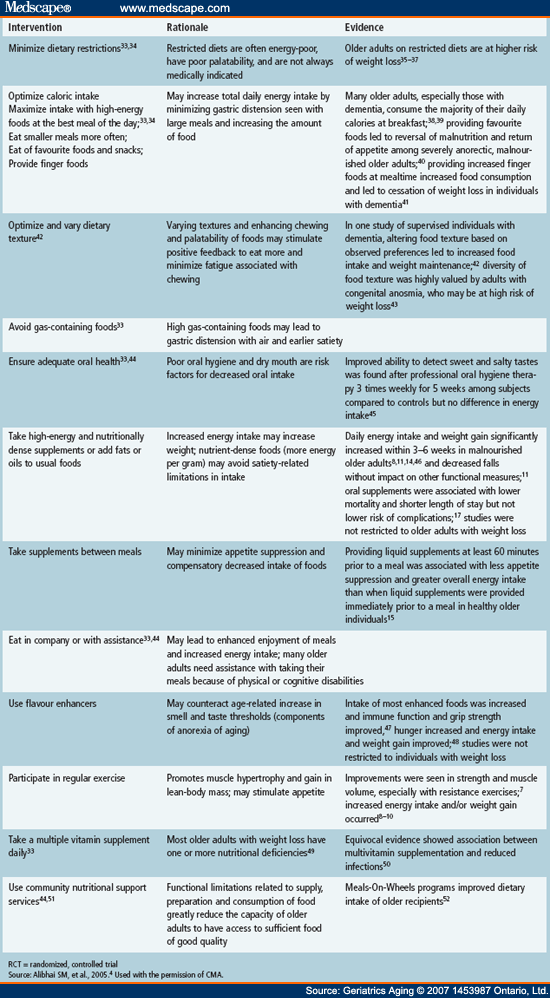

Unintentional Weight Loss in Older Adults

From 10 to 17 years before death, participants lost an average of 0. During the last 9 years of life, the rate of weight loss was faster, and participants lost an average of 0. Model includes no intercept term, so that coefficients can be interpreted directly for each age group. P values represent differences from zero based on 2-sided t test. Knot placements were estimated by using a likelihood ratio testing approach, with the last integer valued knots that were significantly different from the best-fitting knot at the 0. Indicates that the model would not converge at the next value beyond this knot point.

Results from both the quadratic model model 2 and the 3-period model model 5 estimated for each age group are directly compared in Figure 2. In participants aged 60—69 years at death, results are similar until approximately 5 years before death, when the 3-period model suggests a departure from the quadratic pattern, namely, significantly steeper weight loss 1.

In participants aged 70—79 years at death, the 3-period model also shows a departure from the quadratic model, with a significant change in the slope of weight decline 18 years before death and again 7 years before death. Similarly, in participants aged 80—89 years at death, the 3-period model shows significant changes in slope at 3 and 16 years before death. Finally, for participants aged 90 years or older at death, the only significant change in slope occurs 10 years before death, but the overall pattern of weight change is similar to that predicted by the quadratic model.

It is notable that weight at death decreased with age, from Predicted weight in kilograms by time to death and age at death for male decedents from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, Maryland, — Refer to the Statistical Analysis portion of the text for a description of the models. Additional analyses were stratified by cause of death Figure 3. Age groups were combined when too few deaths were available for model convergence within single age groups.

For cancer, weight loss accelerated significantly at 3 years before death, regardless of age group. Participants aged 60—79 years lost an average of 2. For CVD, the best-fitting inflection point increased with age, from 5 years in participants aged 60—69 years to 9—10 years in those aged 80 years or older. In participants aged 80—89 years, weight loss increased to 0.

- diet plan for acidity problem!

- green bean fat loss!

- How much weight loss is a concern?!

- Unintended Weight Loss in the Elderly.

Similarly, in participants aged 90 years or older at death, weight loss increased to 0. Predicted weight in kilograms by time to death, age at death, and cause of death for male decedents from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, Maryland, — Complete results from sensitivity analyses evaluating potential bias due to informative missingness are provided in the Web Appendix. Across all alternative scenarios, our main finding was consistent: Weight loss likely begins earlier than previously thought, and the 3-period model model 5 was supported as the best fitting for the majority of age and cause-of-death subgroups.

Additionally, the best-fitting knots identified under alternative missing assumptions were within the confidence intervals from the main analysis for the majority of age and cause-of-death subgroups under all but the most extreme scenario imputation 4, assuming 2. In all alternative scenarios, the location of the second knot k 2 for this group was outside the confidence intervals estimated in our main results.

However, the coefficient on this term was small and nonsignificant in both the main results and all imputation scenarios. We infer that this difference does not substantively affect interpretation of the results. Two imputation scenarios imputations 2 and 4 also found a difference in the location of the best-fitting first knot k 1 for deaths occurring between ages 80 and 89 years, with the best-fitting knot occurring 9 years before death. Although the best-fitting knot identified in the main analysis occurred at 3 years before death, preliminary analysis also identified a local maxima in model fit 9 years before death, providing some support for this additional knot.

With the exception of these 2 changes, large deviations in knot placement were observed under only the most extreme assumption of informative missingness imputation 4 , which assumed that all participants missing data in the last 3 years of life had experienced a 2. We observed great heterogeneity in weight change trajectories across participants. A model that describes these trajectories as 3 periods, characterized by weight stability or weight gain followed by mild and then accelerated weight loss before death, was consistently supported by the data.

This model provided the best fit across all ages and demonstrated important differences from a quadratic model that postulated more gradual change in weight with age. Weight loss associated with cancer mortality was confined to the last 3 years before death across all age groups, which may reflect direct consequences of the disease Interestingly, an end-of-life weight decline was also prominent in CVD deaths, with accelerated weight loss beginning on average 8—10 years before death for deaths after age 70 years.

Other deaths were associated with extended periods of weight loss of at least 6 years, although noncancer, non-CVD deaths were rare before age 70 years. Differences in weight change by age group may be due to systematic differences in cause of death between age groups, with cancer mortality more common at younger ages and other causes of death more frequent at older ages.

When all ages and causes of death were combined, the average curve was similar to that observed for CVD, the most frequent cause of death in this sample. For participants who died at ages 80—89 years, evidence was found for best-fitting knots at 3, 9, and 16, which roughly correspond to the most predictive knots identified for cancer, CVD, and other deaths.

Furthermore, within cause-of-death groups, knot locations were relatively similar across age groups above 70 years. Alternately, differences in weight change by age group may result from rising instability in energetic equilibrium with age 16 , Because the prevalence of disease increases at older ages, individuals may lose homeostatic capacity and become more susceptible to the catabolic effect of chronic morbidity.

Among persons who died at ages younger than 90 years, we observed a period of terminal drop in weight before death. Above age 90 years, large declines in physiologic reserve may lead to continuing gradual weight loss, regardless of illness severity. This is consistent with the notion that, in very long-lived individuals, cause of death may not be easily recognizable, reflecting progressive multisystem dysregulation and increased vulnerability to stressors more than any single condition.

Previous research has extensively documented that weight loss, particularly unintentional weight loss, is associated with increased mortality in older persons 2 , 8 , 18— Importantly, research has also shown that the association between body mass index and mortality is stronger based on midlife weight than on old-age weight 21 and reverses between middle age and old age: at younger ages, those with high weight have the highest risk; at older ages, those with low weight have the highest risk 8.

These findings suggest that the biologic process that eventually leads to death in older persons is paralleled by progressive weight loss. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the duration, pattern, and severity of weight loss prior to death. This study has several strengths.

Depression

First is the frequency of weight measurements and the length of follow-up, including an average of 8 observations per person beginning an average of 19 years before death. Third, an innovative statistical approach was used to characterize the natural history of weight loss in a flexible way that utilized all available data. This study also has limitations.